Contents

Introduction

Miles and points enthusiasts generally fall into one of two camps: luxury travelers and economy travelers. Because “value” is often tied to market price, the luxury travelers generally flaunt greater redemption values as they are able to spend a marginal number of additional points for a first class ticket or opulent hotel stay that has a substantially higher open-market price. The flaws with this reasoning become apparent when analyzed within the context of economic theories of value.

Theories of Value

There are multiple theories within the field of economics that attempt to explain the price of goods and services. All theories are similar in the sense that they attempt to define and determine “value.” Two of these theories are discussed below.

Supply and Demand

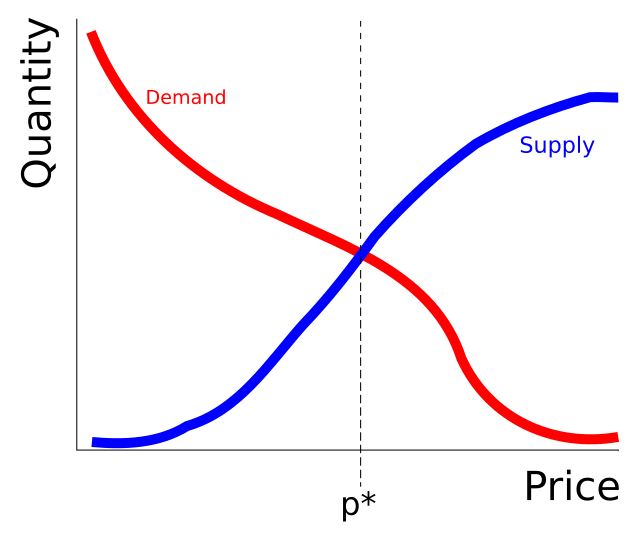

Classical supply and demand based theories define the value of a good or service based on its competitive market price and nothing more. This is generally the approach the travel hacking blogosphere takes when determining a cent-per-point (cpp) based redemption value. If someone spends 160,000 United miles for an $8,000 first class ticket on Korean Airlines, the redemption “value” would be 5 cpp [($8,000*100)/160,000)].

This method is inherently flawed, primarily because the comparison is between a non-cash based metric (miles or points) and cash. If you would never pay $8,000 out of your own pocket for that first class ticket, or $8,000 for the miles that allow you to purchase the ticket, how can you reasonably report a valuation based on that amount? In a perfectly efficient and competitive market, the price of a good or service fluctuates based upon supply and demand. Gasoline shortage? Price goes up. Simple. Using this concept in my example from the paragraph above, if you would never pay 5 cpp for United miles, you should never be reporting that as your redemption value, as this is comparing efficient-market based principles to an inefficient market that is easily manipulated. Airlines can throttle back redemption space making points impossible to redeem for the flights you want, or change redemption terms unannounced.

Intrinsic Value

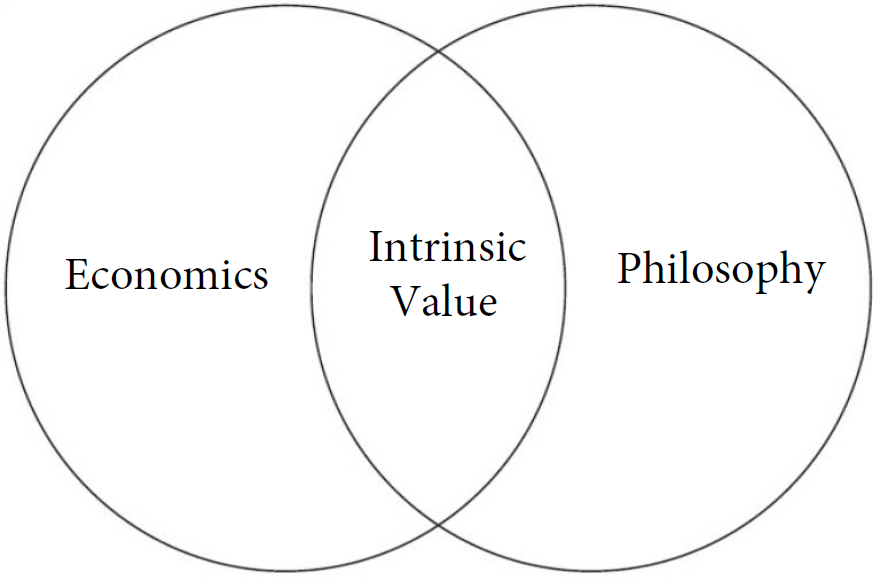

Other theories combine emotion and/or usefulness of a good or service into account along with price, making “value” inherently subjective. If the grocery store has a sale on ground beef, that sale would provide little value to a vegetarian. The issue is that you can’t easily quantify emotion or usefulness. If resources (miles and points in this case) are finite and one person gets three economy flights to another person’s one luxury flight out of the same number of miles, who got more “value?”

Picture a Venn diagram with philosophy on one side and economics on the other. In the middle we can place “intrinsic” value, or the value that something has that takes into account intangibles that go beyond price. Gold is often the foremost example of intrinsic value, as even without a market, the element has inherent value as a material since it doesn’t corrode, can be melted over a flame, and is a fantastic conductor. Some argue that even gold has no intrinsic value since it can’t be consumed (eaten) for survival. Even food has varying degrees of intrinsic value since people can value the extension of human life differently.

Despite the chicanery that comes with point valuations presented by bloggers (The Points Guy, View From the Wing, One Mile At A Time, etc.) who are paid by advertisers to make points appear more valuable than they are and to perpetuate their own lifestyle brand, YOU are able to determine an intrinsic value for points based on the value that YOU as an individual believe they hold. I view this as a combination of the cash-based point redemption value and the experience value. Though this is semi-quantitative at best, the only reason we need to quantify things in this hobby is for comparison to the behavior of others. To create relative value.

Subjectivity in Valuation

Here is a personal example. I once flew in economy from San Francisco to Kayseri, Turkey with a 15-hour layover in Toronto and a 2-hour connection in Istanbul. I was a mess for days after the trip, which significantly impacted the experience during my first few days in Turkey. Had I flown in business or first class and been able to sleep at all over that 30+ hours worth of travel, the value I got out of the first few days of the trip would have been enhanced, and my redemption value would have been significantly higher for reasons that go beyond the cash-price of the ticket.

Maybe you are an aviation geek that has never flown on an A-380, and the cash-based point redemption value on the route you want is lower for flying an A-380 on one carrier vs. flying a 777-200ER on another carrier. That experience of flying on the A-380 carries value to you. Is it 0.2 cpp in added value or 2.0 cpp in added value? Only you as a subjective, decision-making consumer can decide.

Or let’s say you just lost your job and have little expendable cash. Redeeming your United miles at 1.0 cpp market value to fly in economy and save cash on your way home to beg your parents for money probably carries a lot more value than choosing between an A-380 or 777.

We can run this analysis a million ways, but each way is going to be inherently subjective. If you are a cash-poor and points-rich graduate student, maybe you splurge on the luxury of flying in the front of the plane. But understand that decision has an opportunity cost that generally goes undeclared by people throwing around cpp valuations.

Absolute vs. Relative Value

So why do we at US Credit Card Guide still provide our own take on a cpp-based valuation of points within each of the major loyalty programs? We are doing our best to provide a metric that communicates relative and not absolute value to readers. When we say the “value” of a Hilton point is 0.5 cpp and the “value” of a Hyatt point is 1.8 cpp, it is so readers of this credit card guide website understand that an individual Hyatt point can provide a lot more relative value when compared to an individual Hilton point. Sure, it’s flawed. But we do our best to explain the basis of each valuation in terms of the context of this post and rarely if ever provide those valuations in a vacuum.

We do not have affiliate links. You can click through our referral links if you appreciate our content (and we love when you do!), but take my word for it that nobody is getting rich that way. When we write something, it is always relative to the experience and data of our contributors.

Summary

The next time you’re on r/churning and see folks arguing about cpp valuations, try to remember the subjectivity of each decision and what is gained or lost by making that decision. Read the big travel blogs if you’re so inclined, but do so with an inherent skepticism. When someone with something to gain tries to sell you on “value,” the value for the salesman is often nonequivalent with the value you gain as the consumer. Above all, be familiar with your options and clearly define your goals before making a decision. If you’re comfortable, you’ll be more confident that the decision you made is the right one for you, regardless of what anyone else thinks.